Sony NWZ-F886 Review - Sound Quality Review

Sound Quality

Sony brings high-res audio to the masses with this innovative Walkman

Sections

- Page 1 Sony NWZ-F886 Review

- Page 2 Sound Quality Review

- Page 3 Verdict Review

We ‘re going to kick off this section by looking at the process of actually sourcing Hi-Res Audio content. You might think this would have gone better in the Set Up section, but while the sort of issues we’re about to get into aren’t directly related to the F886‘s sheer sound performance, they do seem part and parcel of actually achieving its best performance. As in, any hi-res audio product needs the right sources to deliver on its hi-res claims.

As part of our tests of the F886, we picked on two (2L and 7Digital) of the eight hi-res audio sources linked to from Sony’s Hi-Res Audio online hub as our sources of Hi-Res Audio files. And having selected a few tracks, the first thing we noticed was how long they took to download; around six minutes for a single 168MB nine-minute Mozart track using FLAC 96kHz and nearly 10 minutes for the 330MB 192kHz FLAC version.

These sort of file size and download times are bound to remain stumbling blocks to Hi-Res Audio adoption for some people, even if the world is more geared up for large file management (thanks to cheaper bulk memory and generally faster broadband connections) than it has been before.

Trying to play our downloads presented another problem. For along with the FLAC versions of the Mozart track we’d also downloaded – at £4 each – DSD 64 and DSD 128 versions. But neither of the DSD 64 or DSD 128 track versions actually loaded onto the F886. Instead we got an error message saying they weren’t recognised when we dragged them onto the drop folder.

There’s nothing on the 2L site to explain that DSD tracks might not work on the F886, and Sony’s own compatibility list on its Hi-Res Audio hub suggests that DSD files should work fine. Yet we only found out about the problem after spending £8. Thank goodness we didn’t splurge out on full DSD albums!

This sort of file compatibility issue is precisely the sort of thing we’d hoped the Hi-Res Audio ‘standard’ might circumvent, as it’s guaranteed to drive mainstream consumers nuts. Especially when it has the potential to cost them cold, hard cash.

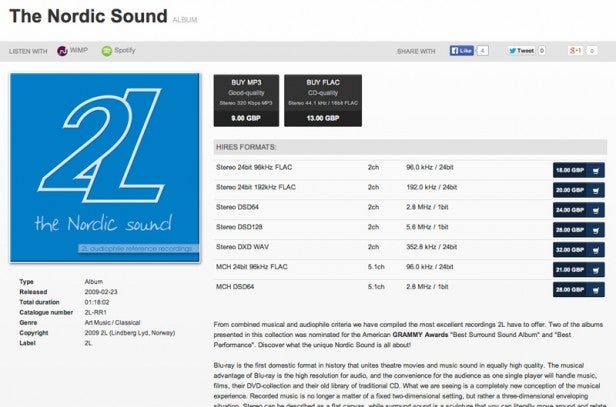

Actually, the amount of cash Hi-Res might set you back is a more general issue, too. On the 2L site you can buy 320kbps MP3 albums for £9, CD-quality (44.1kHz/16bit) FLAC albums for £13, while high-res formats range from £18 for a 24bit, 96kHz two-channel FLAC to a stonking £32 for a Stereo DXD WAV encoded at 352.8kHz/24-bit. Stereo DSD versions cost £24 for DSD64 quality or £28 for DSD128. Individual Hi-Res tracks can cost upwards of £4 a pop too, versus under £2 for a 320kbps MP3.

Thankfully the situation was considerably less painful on 7Digital. Here you could get the 24-bit FLAC version of Radiohead’s King Of Limbs album for £9, while the normal 320kbps MP3 version is £5.

The 2L site underlines the format issue discovered with the DSD downloads, too. It presents you with no less than seven different high-res versions of the same tracks – five stereo, two multi-channel. We guess most folk could figure out for themselves that the multichannel mixes won’t be necessary/work on a stereo device like the F886. But as noted earlier, there’s no readily available information to tell you what will work on the F886 and what won’t.

Another problem likely to be faced by many would-be Hi-Res Audio devotees is that in classic Apple style, FLAC files don’t work in iTunes. This is so big of an issue that we’ve devoted a separate section to it, in the Also Consider part of the review.

One last issue affecting the sourcing of high-res files is availability. Things are certainly a lot better than they were only 12 months ago; Sony’s own Hi-Res Audio hub carries links to eight different sources including Linn and Naim as well as the 2L and 7Digital sites we’ve been exploring, and we fairly easily found a couple more via Google (including the rather handily named highresaudio.com). However, while things are improving, the odds currently remain very much against pop and rock fans finding a favourite album or song available for download in any sort of Hi-Res format.

The over-riding feeling we’ve taken from our experience of hunting down Hi-Res Audio content has been that it’s an industry that still seems too disjointed and confusing to meet the ease of use, content provision and even pricing demands of the mass market Sony is hoping to lure into high-res audio with products like the F886. At the very least, if the music industry wants to get serious about high quality audio, it needs to start mastering everything in high-res.

But does it really matter anyway? Are the charms of Hi-Res Audio really profound enough to make a difference on a music player as affordable and convenient as the F886?

Thankfully, the F886 proves in pretty emphatic fashion that Hi-Res Audio really can make a profound difference to a ‘convenient’ listening environment.

As a simple test of the Hi-Res Audio theory, as noted already we downloaded Mozart’s Violin concerto No. 4 in D Major from 2L in 320kbps MP3 form, 96kHz 24-bit FLAC form, and 192kHz 24-bit FLAC form (plus, pointlessly as it turned out, DSD versions), as well as Radiohead’s entire The King of Limbs album from 7Digital in both 24-bit FLAC and 320kbps MP3 format (let’s not forget in passing that 320kbps is actually much higher than the 192kbps some music software lets you rip your CDs at).

Starting with the Mozart, there’s a very clear improvement in sound quality with each step up the three-rung quality ladder you take. The MP3 is revealed by the other formats to be hissy and thin in terms of the range of sound it delivers, resulting in some pretty unpleasant harshness and distortion when there’s any sort of density in the instrumentation.

With the 96kHz FLAC the hissing disappears pretty much entirely, and there’s a palpably warmer, more well-rounded and more ‘finished’ feeling to the sound that leaves it almost free of harshness and also much more consistent in the quality you hear. By which we mean you don’t hear the sound ‘cramp up’ more during the denser moments like you do with the MP3.

At 192kHz, though, things truly become spectacular. The audible range is clearly extended, there’s much more subtle detail — little clicks, taps and breaths from the orchestra, for instance — and the whole soundstage feels much more open and dynamic, with no clipping, harshness or bias even in the very highest parts of the treble range. In short, the whole thing sounds more like an original orchestral performance and never once sets your teeth on edge with obvious compression or muddiness.

With the Radiohead album, while you don’t have such extreme trebles to draw comparisons with as you do with the Mozart piece, the benefit of the FLAC files over the 320kb MP3s is still considerable. Again there’s more detail and range in the mix, as well a greater sense of stereo separation without, crucially, the sound ever starting to lose cohesion. The whole album sounds more open and overwhelming, enabling you to get completely immersed in the music’s dense soundscapes. Or to put it another way, with FLAC it’s like the whole album has been turned up to 11…

That this difference is so apparent even using a relatively mass market player like the F886 is undoubtedly a testament to the quality of Sony’s engineering. But it also, crucially, proves the point Sony wants to make that Hi-Res Audio needn’t be – indeed, shouldn’t be – exclusively the domain of ultra-rich audiophiles who spend thousands of pounds on amps and speakers to shove in dedicated listening rooms. Hi-Res Audio really can make a significant difference to your enjoyment of music even with a portable product that costs just £260.

As discussed earlier, to get the full Hi-Res Audio experience you should combine the F886 with a pair of Hi-Res certified headphones. However, while we did precisely that for most of our testing, even using the supplied and rather basic in-ear headphones we could very easily discern the difference in quality delivered by the higher-res file formats.

With respect to areas of the F886’s performance not directly related to its Hi-Res Audio capabilities, the noise-cancelling option works quite well with simple, flat aeroplane and train noise, but isn’t as adept at keeping out all sound as good on-ear noise cancelling headphones tend to be.

As for the speakers built into the F886, while they’re welcome in principle and can actually go quite loud, they’re rather tinny and thin. Certainly it’s no replacement for even a half-decent external speaker system, and doesn’t play any part in the Hi-Res Audio story.

As a video and photo player the F886 is also very accomplished, thanks to the impressive clarity, colour richness and even contrast of its screen. The glassy front is a bit reflective in direct light, but the screen is capable of going bright enough to combat all but the most extreme bright conditions reasonably well – though obviously running the screen brightly heavily impacts battery life, so try not to leave it set too bright all the time.

Talking of battery life, this is another strength of the F886. For if you stick with the default screen brightness and avoid using the speakers you’ll get surprisingly close to the 26 hours of battery life for Hi-Res Audio playback Sony claims for its groundbreaking little device. (Though it’s startling to note that battery life increases by almost 10 hours if you only use normal MP3 files!)