Why the Psion Series 5 belongs in the gadget hall of fame

OPINION Andy Vandervell insists that the British-made Psion Series 5 is one of the greatest gadgets ever made

When one my colleagues suggested we dedicate a whole week of coverage to the Best of British tech, I had only one thought – the Psion Series 5. Britain hasn’t produced many iconic consumer gadgets, but the Series 5 is right up there among the greats.

Released in 1997, the Series 5 was the culmination of over a decade of development in personal organisers and PDAs (Personal Digital Assistants). And, much like the iPads and iPhones of today, it was the result of tight integration of software and hardware.

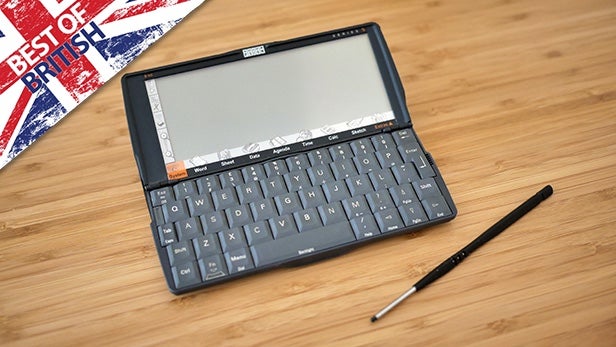

Psion designed the hardware and software in tandem, creating a handheld computer that weighed just 350 grams and lasted between 10 and 20 hours on two AA batteries. Sure, its 5.6-inch, 640 x 240 16 greyscale display was limited and next to useless in direct sunlight, but the Series 5 was a revelation in its time.

This genius little gadget came with richly-featured word processing, spreadsheet, and agenda software, printed and transferred files wirelessly (using IR) and could slip into a large pocket. Later versions added a web browser and email applications, but the key feature was always the brilliant keyboard and the ingenious clamshell design.

Even now the keyboard is a minor miracle. A Series 5 I picked up from eBay for £40 still has a perfectly functioning keyboard – it’s too small to touch type on, but it’s large enough that you can type comfortably in places that are just impractical for anything else. Nothing before or since has quite captured the same magic.

(Said Series 5 also suffered from the notorious screen cable failure that has killed many a Series 5 over the years. It’s not an easy thing to fix, which is why there are no shots with the screen on. It’s nearly 20 years old, so I can forgive a few issues.)

Efficiency was another key element of the Series 5’s success. The EPOC operating system, which would later be spun-off to become the Symbian OS that powered hundreds of millions of mobile phones, was designed to work with as little memory as possible.

Yet the functionality wasn’t reduced. Not at all. Psion’s productivity programs supported object embedding, so you could embed graphs, tables and hand drawn jots into documents just as you could on a PC running Windows or a Mac. You could even zoom in and out of any part of the interface to make it easier to read.

For a tiny handheld powered by a lowly ARM processor – another British-designed component – it was an impressive feat.

To understand why this was such a revelation you need to consider the alternatives at the time. The most advanced laptop in 1997 was the IBM ThinkPad 770. PC Magazine described it as “well worth its $7,700 street price” and that it was a desktop PC “that happens to weigh just 8.2 pounds [3.7kg]”. It was also 55mm thick – that’s nine iPad Air 2s – and lasted 3.5 hours on a charge.

It was an impressive machine at the time, but the Psion Series 5 cost less than £500, lasted ages and could still do decent work on the move. Rival PDAs, meanwhile, lacked the keyboard input and software complexity to make them serious work tools. The Series 5 was special.

But it wasn’t special enough to propel Psion to further success. The Series 5 and its derivatives were hugely popular among power users, but they never quite achieved the mass market success of ‘PC companion’ alternatives. Psion was successful and profitable, but not enough to make it immune to powerful rivals and outside pressures.

The killer blow came when the software division was spun-off to form Symbian, the partnership that would develop a common operating system for millions of mobile phones from Nokia and many other brands.

That deal secured Psion’s financial security – no matter the situation now, Symbian was a huge success in its time – but it ripped the heart from Psion’s PDA division. Gone was the tightly integrated software and hardware teams, and subsequently the ability to quickly develop and iterate new products.

Psion would eventually leave the PDA market, but for Psion and Series 5 fans it’s a story of what could have been. As Andrew Orlowski outlines in his outstanding piece commemorating the 10-year anniversary of the Series 5 – a 10-page epic worth reading if you’re interested in the story behind the Series 5 and Psion – Psion is as much a story of missed opportunities as success.

At various times it explored the idea of producing a hard drive-based MP3 player and a standalone sat nav device. Neither of these ideas were followed through, but the man behind the MP3 idea went on to become VP for Hardware Engineering at Apple for the iPod and iPhone, while several Psion alumni were behind the meteoric rise of TomTom.

It’s a stretch, I think, to believe that such products would have rescued Psion’s consumer division. Apple wasn’t the first to produce a hard drive MP3 player, after all, merely the first to successfully market the idea and sell it to the labels.

Had the software division not disappeared to work on Symbian, it might have been well-placed to compete with the likes of RIM and Nokia, but there were plenty of other obstacles to that path, too.

So the Series 5 didn’t propel Psion to the success it arguably deserved, but no one could ever convince me it isn’t one of the most ingenious, iconic gadgets I’ve ever used. It’s a classic and British made one at that.