Death by Driverless Car: We investigate who’s to blame when robot cars kill

It’s the year 2025. Your driverless car has just crashed into a tree at 55mph because its built-in computer valued a pedestrian’s life above your own. Your injuries are the result of a few lines of code that were hacked out by a 26-year-old software programmer in the San Francisco Bay Area back in the heady days of 2018. As you wait for a paramedic drone, bleeding out by the roadside, you ask yourself – where did it all go wrong?

The above scenario might sound fanciful, but death by driverless car isn’t just inevitable – it’s already happening. Most recently, an Uber self-driving car hit and killed a pedestrian in Arizona, while in May 2017, semi-autonomous software failed in a similarly tragic way when Joshua Brown’s Tesla Model S drove under the trailer of an 18-wheel truck on a highway while in Autopilot mode.

Tesla admits that its system sensors failed to distinguish the white trailer against a bright sky, resulting in the untimely death of the 40-year-old Floridian. But Tesla also says that drivers need to keep their hands on the wheel to stop accidents like this from happening, even when Autopilot is activated. Despite the name, it’s a semi-autonomous system.

Uber, on the other hand, may not be at fault, according to a preliminary police report, which lays the blame on the victim.

It’s a sad fact that these tragedies are just a taste what’s to come. In writing this article, I’ve realised how woefully unprepared we are for the driverless future – expected as soon as 2020. What’s more worrying is that this future is already spilling out into our present, thanks to semi-autonomous systems like Tesla’s Autopilot and Uber’s (now halted) self-driving car tests.

Tomorrow’s technology is here today, and with issues like ethics and liability now impossible to avoid, car makers can’t afford not to be ready.

What happens when a driverless car causes an accident and, worse still, kills someone?

Understanding death by computer

To tackle liability, we need to ask how and why a driverless car could kill someone. Unlike humans, cars don’t suffer fatigue, they don’t experience road rage, and they can’t knock back six pints of beer before hitting the highway – but they can still make mistakes.

Tesla’s Model S features semi-autonomous Autopilot technology

Tesla’s Model S features semi-autonomous Autopilot technology

Arguably, the most likely cause of “death-by-driverless-car” would be if a car’s sensors were to incorrectly interpret data, causing the computer to make a bad driving decision. While every incident, fatal or otherwise, will result in fixes and improvements, tracing the responsibility would be a long and arduous legal journey. I’ll get to that later.

The second possible cause of death-by-driverless-car is much more difficult to resolve, because it’s all about ethics.

Picture this scenario: You’re riding in a driverless car with your spouse, travelling along a single-lane, tree-lined B-road. There are dozens upon dozens of B-roads like this in the UK. The car is travelling at 55mph, which is below the 60mph national speed limit on this road.

A blind bend is coming up, so your car slows down to a more sensible 40mph. As you travel around the bend, you see that a child has run out onto the road from a public footpath hidden in the trees. His mother panicked and followed him, and now they’re both in the middle of the road. It’s a windy day and your car is electric, so they didn’t hear you coming. The sensors on your car didn’t see either of them until they were just metres away.

There’s no chance of braking in time, so the mother and child are going to die if your car doesn’t swerve immediately. If the car swerves to the left, you go off-road and hit a tree; if the car swerves right, you hit an autonomous truck coming in the opposite direction. It’s empty, so you and your spouse would be the only casualties.

In this situation, the car is forced to make a decision – does it hit the pedestrians, almost certainly killing them, or does it risk the passengers in the probability that they may survive the accident. The answers will have been decided months (or even years) before, when the algorithms were originally programmed into your car’s computer system – and they could very well end your life. While the car won’t know it, this is in effect an ethical decision.

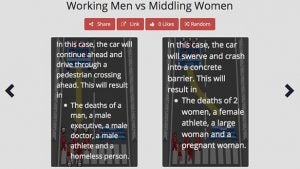

To demonstrate the overwhelming difficulty of coding ethics, have a go at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Moral Machine. It’s a quiz that aims to track how humans react to moral decisions made by self-driving cars. You’re presented with a series of scenarios where a driverless car has to choose between two evils (i.e. killing two passengers or five pedestrians) and you have to choose which one you think is most acceptable. As you’ll quickly realise, it’s really hard.

Which scenario would you choose? MIT’s Moral Machine is a self-driving nightmare

Which scenario would you choose? MIT’s Moral Machine is a self-driving nightmare

If all of this scares you, you’re not alone. In March, a survey by US motoring organisation AAA revealed that three out of four US drivers are “afraid” of riding in self-driving cars, and 84% of those said that was because they trusted their own driving skills more than a computer’s, in spite of overwhelming evidence that suggests that driverless cars are significantly safer – human error is the biggest killer on our roads, after all.

So why are we so afraid? I asked Prof. Luciano Floridi, Professor of Philosophy and Ethics of Information at the University of Oxford, that very question.

“I think it’s an ancestral fear of the unknown, fear of machines. It was the Golem and Frankenstein, and now it’s a technology that we don’t fully control in the case of driverless cars,” Professor Floridi tells me. “It also seems to be, perhaps, a mis-selling on the side of the industry, where total safety is sold as a possibility, which we know is not the case. Nothing is 100% safe, you can only be safer.”

So even though driverless cars are safer and reduce a person’s chance of death, drivers struggle to accept the idea that they could be killed by a machine, rather than by human error.

The greater good vs your safety – who wins?

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently surveyed 2,000 people and found that 76% of respondents would expect a driverless car to prioritise the safety of a group of ten pedestrians over a single passenger. Very noble, right? In ethics, this is called “utilitarianism” – that’s shorthand for when decisions are made for the greater good.

But humans are animals, and that means evolution has wired us to protect ourselves and those who are important to us, often at the expense of the “greater good”, whatever that may be.

Tellingly, when MIT’s respondents were asked to rate the morality of that same driverless car – the one that would crash and kill its owner to save the pedestrians – as if they themselves were a passenger in the vehicle, the morality rating of the “ethical” car dropped by a third.

The moral of the story is no great surprise – we all like the idea of utilitarian driverless cars, until we have to ride in one. This self-preserving belief system will have an acute effect on the driverless car industry. For instance, what if car makers start selling their vehicles on an ethical basis? Could some cars be designed to always strive for a “greatest good” result, while others are built to act in the interests of the driver or passengers?

But, while Professor Floridi believes ethics will play some part in marketing driverless vehicles, he isn’t convinced they’ll be sold based on their moral code:

“That would be such a bad move on the advertising side of things. What we will see, however, is some ethical component in advertising at large. If you remember when cars started being advertised as safer because of safety belts, companies saying it was so much safer if you’re in an accident. It will be like that. Not that this ethical code is better than that ethical code.”

Professor Luciano Floridi thinks ethics is one of the biggest roadblocks to the driverless car future

Professor Luciano Floridi thinks ethics is one of the biggest roadblocks to the driverless car future

Are driverless cars impossibly complicated?

Unfortunately for us all, Floridi tells me, driverless cars are ill-equipped to tackle such complex decisions. He believes that despite all of the research and development efforts focused on bringing driverless cars onto our roads, computers are inherently unable to handle the complex moral decisions that driving demands.

“The ethics is delicate, too subtle, too open-ended for an ordinary driverless car,” he explains. “The car I need to go from the countryside to London, or from London back to Rome, as I did when I was a young guy with not much money – can you imagine that journey? Around 2,000 miles from Oxford to Rome and back? In a context where anything could happen, it’s very hard to imagine a totally uncontrolled environment with a driverless car being successful, without me having a chance to pick up the wheel.”

Floridi says that it’s “impossible” to create an algorithm that can emulate human ethics on the road, because there are an infinite number of possible scenarios that can arise when driving. He gives the example of a cat in the road:

“You could say ‘stop every time’ there’s a cat – unless what? Unless there’s a big truck driving at 70mph behind you, and you have your kids in the car. At that point you say ‘go and kill the cat’, because your family is at risk. You can multiply this with ‘only if’ and ‘unless’ to an endless number of conditions.”

Why is it so difficult? Well, it’s very easy to computerise a closed world, where we can understand every single condition. But driving is an open-world scenario, where the conditions are random and impossible to predict, which makes it very hard to computerise. It’s because of this that Floridi believes there’s no hope for driverless car software to be sufficiently ethically competent, at least on existing road networks:

“Imagine playing chess with someone who picks up a gun at some point, out of his pocket, and says ‘you can’t make that move,’” jokes Floridi. “That’s a different kind of chess. No computer can do anything about it, no matter what we’ve put into it.”

Floridi says that to tackle this, car companies are already consulting with ethics experts to make sure their software is morally watertight. I asked for an example, and he told me that he attended a meeting with Audi “where ethical issues were the main topic precisely because of the implications of driverless cars. As any advanced technology that we develop requires, at some point the social impact forces an ethical consideration.”

So who pays up?

OK, so we’re back at the roadside, and the paramedic drone has finally arrived. The bleeding has stopped, you’re lucid once again, and you’re ready to tackle the issue of compensation. You didn’t crash your car; your car crashed itself – who is paying up?

“In criminal law and in civil law, the issue is who is in control of the vehicle,” Matthew Claxson, a road injury lawyer at Slater & Gordon, tells me. “So the operator could say, ‘Well, I was reading a newspaper and relied upon the computer to take control of the journey,’ and there would be an argument that the manufacturer of the car would have the liability. Whether they pursue further claims against software manufacturers remains to be seen.”

Related: Apple CarPlay vs Android Auto

If a car part – like a gearbox, for instance – fails in the UK today, Claxson explains, and the fault was the result of dodgy manufacturing, and that car goes on to kill someone, the estates of the person who died would “usually sue the car driver,” or the car operator in the case of a driverless car. The driver’s insurance company then settles the claim, but would then go on to pursue a further action against the car manufacturer “behind the scenes, to recover their loss.”

“It’s one of the advantages of the UK insurance policy that it gives recourse to those who have been seriously injured or killed to a financial settlement that can either assist with the medical treatment, or pay for the funeral costs, or assist the bereaved families in some way,” says Claxson.

But there’s one issue that throws a spanner in the works, and that’s hacking. Earlier this year, it was discovered that the Mitsubishi Outlander hybrid could be controlled by hackers thanks to a vulnerability in the car’s on-board Wi-Fi system. And more recently, Fiat Chrysler had to issue a voluntary recall for 1.4 million vehicles after a hack that could kill the engine remotely was discovered.

Driverless cars could be hacked and crashed – so who pays up then?

Driverless cars could be hacked and crashed – so who pays up then?

So if a driverless car kills somebody because it’s been hacked, then it doesn’t seem fair to pin liability on the driver or the car maker. In that case, who pays up? Claxson suggests the following solution:

“We have a process in this country where if a car is stolen, and it kills or causes injury to somebody, then that thief disappears (i.e. it’s a hit-and-run), we have an organisation known as the Motor Insurers Bureau, which is a fund of last resort that’s set up by the Secretary of Transport in this country. That would step in for those hit-and-run victims and compensate them if they are the innocent party.”

He continues: “One would hope to see a similar mechanism like that in the future, that if a car is hacked and it’s not the fault of the manufacturer or driver, you would hope there would be a similar fund to assist those victims.”

Driverless cars are a liability nightmare

The message here is simple: It’s pretty easy to assign liability when cars are fully autonomous. And even in the case of hacking, compensation can still be paid out. But what happens when a car isn’t fully autonomous, and the driver can still control the vehicle?

After all, when Joshua Brown died after his car’s sensors failed earlier this year, Tesla quickly reminded us of its advice that Autopilot “is an assist feature that requires you to keep your hands on the steering wheel at all times.” Tesla also added: “Autopilot is getting better all the time, but it is not perfect and still requires the driver to remain alert.”

The starting point is working out exactly how autonomous a vehicle is. There are plenty of different methods to do this, but the most popular (so far, anyway) is the SAE system, which has six different levels of vehicle automation:

Level 0 – No Automation – The full-time performance by the human driver of all aspects of driving

Level 1 – Driver Assistance – The driving mode-specific execution of accelerating, decelerating, or steering, using information about the environment

Level 2 – Partial Automation – The driving mode-specific execution by one or more driver assistance systems of both steering and acceleration/deceleration

Level 3 – Conditional Automation – Performance by an automated driving system of all aspects of the driving task, with the expectation that a human driver will respond to a request to intervene

Level 4 – High Automation – The performance by an automated driving system of all aspects of driving, even if a human driver doesn’t respond to a request to intervene

Level 5 – Full Automation – The full-time performance by an automated driving system of the entire driving task, under all road and environmental conditions that can be managed by a human driver

Related: What is Tesla Autopilot?

Even new cars aren’t hitting level 5 autonomy yet, and there are plenty of cars on the road that still haven’t made it past level 0. That means that under existing law, if your car has an accident because you didn’t have your hands on the wheel, even in a semi-autonomous car, you’re almost certainly liable, at least according to Adrian Armstrong, of the Collision Investigation team at forensics firm Keith Borer Consultants:

“Currently, it’s the driver’s fault. All of the safety features that are added, take the Tesla for example, are designed to be an addition to the driver’s input. They are not supposed to replace the driver’s awareness.”

But as the Tesla case has proved, as cars become more autonomous, it becomes significantly more difficult to assign liability.

Nvidia’s DRIVEnet demo, which shows car sensors tracking objects in real-time

Nvidia’s DRIVEnet demo, which shows car sensors tracking objects in real-time

The UK Department of Transport currently suggests that liability for a vehicle in autonomous mode rests with the car maker, but when the driver has regained control, the driver should assume liability instead.

The problem is that it’s tough for drivers to stay mentally engaged when they’re not physically engaged, which makes that ‘handover’ period difficult to resolve in terms of liability. Some studies have shown that it can take as long as 35 to 40 seconds for drivers to take effective control of a car when switching back from autonomous mode.

Insurance companies are (unsurprisingly) very keen to crack the matter of liability with awkward situations like the handover dilemma. One insurance firm that’s already making significant headway in the space is AXA, as Daniel O’Byrne, the company’s Public Affairs Manager for the UK, explains:

“We are a partner in three of the government-funded trials that are looking to bring driverless or connected or autonomous vehicles to fruition. We’re taking the modified Bowler Wildcat, which is already capable of being driven under remote control, and was developed militarily by BAE. We’re trying to take it to the next level with the sensors and the decision-making process, and where we come in is looking at that from an insurance liability perspective.”

O’Byrne says that the company is particularly interested in how liability is assigned during the handover period. After all, he tells me the government “eventually wants you to be able to read a book or check e-mails on an iPad”, adding: “I’d be very surprised if by 2020, you can’t just press a button in your car and start reading a book.” But that is a huge problem, because it means the “driver” isn’t paying attention to the road environment:

“If the car hands over control to the human, how long is it reasonable to allow that driver to assume liability again? Can a driver go from reading a book to driving at X miles an hour in five seconds? That’s probably unreasonable. We are looking at that behavioural aspect, the universities are looking at the psychology, and how people react to that handover.”

Watch: Autonomous liability debated

Unlike in the US, there’s no law in the UK that says you have to keep your hands on the wheel. What we have in Britain is the Road Traffic Act, which only compels drivers to pay “due care and attention.” That sounds like frustratingly broad phrasing, but O’Byrne believes this ambiguity could actually give the UK an advantage against other countries when it comes to building a legislative framework.

“We were signatories to, but not ratifiers of, the Vienna Convention,” says O’Byrne, referencing the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, which says that drivers must always keep their hands on the wheel. “And, in a nutshell, whilst the Road Traffic Act says you have to pay due care and attention, we are not as prescriptive as other countries saying that you have to keep your hands on the wheel at all times, which potentially allows us an easier change in the law than, say, Germany.”

The Venturer Consortium, which is the driverless car trial group that AXA is part of, is currently testing driver’s performance during the handover process in different scenarios. The results of this trial are going to be extremely useful in working out who is liable, and will hopefully reveal how long a driver reasonably has to regain full control of a vehicle.

Once the insurance companies and legislators come to a joint conclusion on this, it should be easier to set a standard length of time for drivers to regain control of a driverless vehicle. That should make it significantly easier to determine who’s liable, because the switchover from autonomous systems to driver control can easily be tracked on a software level. And that means assigning blame is almost as easy as it is today.

Bowler Wildcats are currently modified for driverless car tests in the UK

Bowler Wildcats are currently modified for driverless car tests in the UK

Are driverless cars worth all this effort?

Let’s be fair: When industry giants like Tesla, Google, and Ford tell you that we’ll be safer with driverless cars, they’re absolutely right. As cars begin to rely less on human input, fewer humans will die on roads.

According to OECD data, a fatality occurs once for every 53.4 million miles driven by cars, as an average across 20 EU countries sampled. In the United States, better-than-average road safety standards reduce that figure to one fatality per 94 million miles. But already, over 130 million miles have been driven with Tesla’s Autopilot activated, with just a single fatality on the books.

Part of the allure of driverless cars is the fact that it snuffs out human error, which AXA believes accounts for 94% of all driving accidents. The CDC says over 30% of road fatalities in the United States involve alcohol. And in the United Kingdom, the Department for Transport puts that figure at around one in six. If we wake up tomorrow and every car is autonomous, drink driving disappears overnight.

It gets even better: According to the Eno Centre for Transportation, if 90% of all vehicles on the roads in the US were autonomous, the number of road accidents would fall from 5.5 million per year to just 1.3 million. That future is not so distant either, with the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers predicting that by 2040, around 75% of all vehicles will be fully autonomous.

The biggest challenge to driverless cars going mainstream is getting the public on side. Without proper solutions for the issues around ethics and liability, public opinion is sure to stay frosty for the foreseeable future.

Car makers can talk up the technology until they’re blue in the face, but if a manufacturer can’t tell a grieving wife why her husband’s hatchback just drove him off a cliff – or even cough up the compensation – then driverless cars will probably be passenger-less too.

This article was originally published in 2016. At that point, Tesla did not respond to our interview request.

Would you welcome a driverless car future? Tell us your thoughts by tweeting us @TrustedReviews.