Optoma 3D-XL Review

Optoma 3D-XL

If you're looking for a cheap route into 3D projection, this is it. But naturally there are strings attached...

Verdict

Pros

- Exceptionally cheap for a 3D product

- Hardly any crosstalk noise

- Compatible projectors are predominantly cheap

Cons

- No remote

- Compatible projectors likely not very good

- 3D effect seems more tiring than most

Key Specifications

- Review Price: £249.60

- Compatible with all mainstream 3D sources

- Works with 3D Ready DLP projectors

- 720p native resolution

- Two HDMI v1.4 inputs

- DLP-Link Shutterglasses supplied

Man, this 3D business is getting complicated. For as well as the mess of passive/active/glasses-less 3D TVs, we now also have the curious phenomenon of 3D-Ready projectors to tussle with.

The first thing to clear up is that if a projector says it’s 3D-Ready, that doesn’t mean you can just plug your Blu-ray, Sky HD/3D receiver or games console straight into it. The 3D Ready term was in fact originally coined to describe DLP projectors – generally startlingly affordable models – capable of handling Nvidia’s 3D Vision PC output system.

The arrival of the Optoma 3D-XL converter box we’re looking at today, though, gets round this old Nvidia-only limitation. For it sits between your 3D sources and a 3D-Ready projector, and converts 3D inputs – be they frame packed ones from a Blu-ray player or side-by-side ones from a Sky box or Xbox 360 – into the frame sequential system supported by the 3D Ready projectors.

At which point many of you are probably feeling a bit confused. After all, don’t Blu-ray players output frame sequential 3D images in the first place?

Actually, no. 3D Blu-ray players use ‘Frame Packing’ – a stacking approach that places 3D’s necessary left and right eye images one on top of the other within a single, extra large frame, leaving display devices with the job of unstacking the two images before sequentially presenting one to the left eye and the other to the right eye. Frame sequential 3D, as used by 3D-Ready DLP projectors, is essentially much simpler. It involves delivering full resolution picture frames to a projector at a 120Hz refresh rate, with frames alternating between the left and right eye content. The projector doesn’t have to do anything more complicated than be able to show a 120Hz signal – providing, effectively, a 60fps image for each eye.

What the Optoma 3D-XL does, therefore, is convert incoming side-by-side (Sky, Xbox 360) and frame packed (Blu-ray) 3D signals into the frame sequential format ready to be fed to a compatible 3D-Ready projector. Such projectors are increasingly common, with Acer, BenQ, NEC and Vivitek all joining Optoma in offering 3D-Ready projection models. Optoma itself now has no less than 14 projectors able to work with the 3D-XL, including the DW318 we’re using for this test.

The key benefit of the 3D-XL approach is, without a shadow of doubt, cost. We’ve found the 3D-XL package going for just £250, which includes a pair of the necessary active glasses. Furthermore, the 3D-Ready projectors the 3D-XL works with tend to cost peanuts compared with the first ‘normal’ 3D projectors we’ve seen from JVC and Sony.

The DW318, for instance, is yours for around £500. So you can get yourself enjoying 3D images of 100in or more for just £750. (Plus the cost of your 3D sources, naturally.)

To be fair, this is to some degree a starting cost. Real 3D fans might also consider adding a ‘silver’ screen to boost the 3D performance, plus, of course, you’re going to need extra pairs of Optoma’s ZD201 glasses if you want to make 3D viewing a family affair.

However, even here there’s a saving of sorts, since the relative simplicity of the frame sequential glasses technology means further pairs of Optoma’s ZD201s cost just £60 each, compared with the £100 or more routinely charged for the extra glasses needed by most full HD 3D TVs.

At this point, many of you are probably starting to think this is all sounding too good to be true. And to some extent you’d be right, for the 3D-XL approach to 3D does come with a fairly heavy-duty string attached: its maximum output resolution is 1,280 x 720 pixels, rather than a full HD 1,920 x 1,080. In other words, your full HD Blu-ray discs will end up being downscaled, leading to an inevitable loss of resolution that could be quite poignant at the sort of large image sizes delivered by projection systems. The picture quality will also be at the mercy of the downscaling engine employed by the 3D-XL box – and given how cheap this box is, it’s hard to imagine this scaling engine being very special.

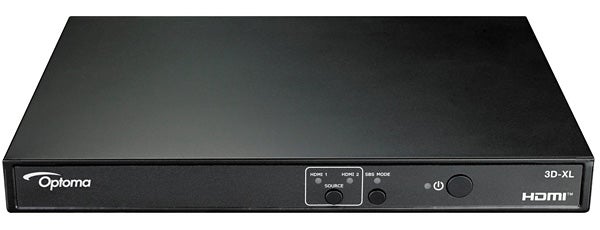

Physically speaking, the 3D-XL is a surprisingly diminutive device, and unstylish with it – essentially it looks like an escapee from the kit rack of a physics lab. Connections to its rear comprise two v1.4 HDMI inputs (with audio support), and a single HDMI output, along with a 9-pin RS-232C control port. To the unit’s fore, meanwhile, are simple buttons for power, input selection, and ‘SBS Mode’ – where SBS stands for, of course, side-by-side. You have to press this to alert the box to the presence of an SBS 3D feed rather than a frame packed one.

And you really do have to press this button. For annoyingly, the 3D-XL doesn’t ship with a remote control. Bang goes our couch potato lifestyle, then!

Firing up the 3D-XL in conjunction with the Optoma DW318 projector and donning the ZD201 glasses is best described as an interesting experience rather than a brilliant one.

On the upside, images from all our 3D sources really do look resolutely 3D, with a depth of field to rival that seen with most of the full HD 3D displays we’ve seen. Even better – and this really is an unexpected pleasure – 3D images look almost completely devoid of crosstalk (double ghosting). Even the notorious Golden Gate Bridge sequence in ”Monsters Vs Aliens” looks as clean as the proverbial whistle. Excellent.

The ZD201 glasses do join many other brands of 3D active glasses in knocking quite a bit of brightness out of the picture, though. Mind you, given that the DW318 projector is apparently designed to push brightness over contrast (black levels look poor if you watch it in 2D mode), the toning-down effect of the 3D glasses is actually quite welcome!

There are bigger issues, though. First, the lack of detail and sharpness of 3D Blu-ray playback compared to what we’re accustomed to seeing on full HD 3D displays is obvious, despite the impressive absence of crosstalk noise. The image looks more like high quality standard definition than full high definition. In fact, the 3D-XL arguably delivers sharper results with Sky’s side-by-side broadcasts – perhaps because these broadcasts are starting out with a lower resolution than the Blu-rays, and so the 3D-XL’s processors aren’t having to work so hard.

It’s perhaps also as a result of the projector’s processing that moving objects on 3D images, especially Sky/Xbox side-by-side ones, can look a touch flickery – as if they’re moving in water.

The biggest problem with the 3D-XL’s 3D results, though, is that they’re just not comfortable to watch. Right away we felt as if our eyes were having to work harder to accommodate the 3D-XL’s 3D images than they do with most other 3D displays. Closer scrutiny of why this might be the case suggests there’s some issue with simultaneously controlling objects in the foreground and background.

The easiest example of what we’re trying to describe here can be seen with a Sky 3D football broadcast. For while the footage of the pitch looks absolutely fine, the channel logo and scores foregrounded in the top corners of the picture look an unfocussed mess until you force/strain your eyes to focus specifically on them (which is, of course, a pretty tiring thing to do if you’re having to do it regularly while watching a 3D image).

With 3D Blu-rays, meanwhile, initially we felt that the depth of field was all over the place, with some background objects actually looking as if they’re in front of foreground objects. Again, this causes quite considerable eye and brain fatigue as you try and resolve what you’re seeing.

Thankfully this situation was improved considerably by activating the DW318’s 3D Sync Invert feature, to the point where watching 3D Blu-rays actually became fun, notwithstanding a few sporadic remaining depth errors.

One last concern that has to be aired here isn’t really the 3D-XL’s fault, but has instead to do with the sort of projectors it’s designed to work with. For it’s an inescapable fact that most 3D-Ready projectors to date appear to be designed more for business and education markets, making them pretty average in AV terms. Certainly as a 2D video projector, the DW318 is very uninspiring.

With this in mind it’s hard to know exactly where the 3D-XL’s problems end and the projector’s problems kick in. But in the end we guess the DW318 can be treated as reasonably representative of the performance with the 3D-XL of at least Optoma’s 3D-Ready projectors, otherwise the brand wouldn’t have sent it to us for our tests.

Verdict

There are some pretty amazing things about the 3D-XL. Starting with its truly startling cheapness. And the fact that it can upgrade some models of projectors you might already own to 3D, rather than requiring you to buy a whole new 3D projector system. Also brilliant is its suppression of 3D’s dreaded crosstalk noise.

However, its 3D effect isn’t entirely convincing at times – or at least it seems to demand more effort from your brain and eyes than we felt entirely comfortable with. Plus we suspect that many of the 3D-Ready projectors it’s intended to partner won’t be much cop aside from their basic 3D readiness.

Trusted Score

Score in detail

-

Value 8

-

Features 6

-

Design 5