William Henry Fox Talbot: A British Technological Pioneer

As we celebrate the best that the British technology industry has to offer this week, we take a look back at a man who helped lay the foundations for photography as we know it today.

Despite what Google will try to tell you, the question “Who invented photography?” is not easy to answer.

Modern photography doesn’t have just one inventor. Instead, it’s a list of names: Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, Steve Sasson. We could add plenty more, but there’s one that you’re guaranteed to hear in every conversation, and that’s William Henry Fox Talbot, a British technological pioneer who revolutionised image-making.

“The work that Talbot did formed the basis of photography until the digital era,” says Michael Pritchard, Director-General of the Royal Photographic Society and avid photographic historian. “He was also visionary in how he saw the application of photography, in terms of documentation and as an art form in its own right.”

Another admirer of Talbot’s is Martin Kemp, Emeritus Research Professor in the History of Art at Oxford University. “By bringing together existing knowledge in optics and chemistry, and working experimentally with a series of subtle and elusive processes – with great persistence and inventiveness – he realised a new concept in the way that the world could record itself as a fixed, naturalistic image,” he says.

So, what did Talbot invent and how?

SEE ALSO: Five smartphone camera features ‘professionals’ will love

Zeil in Richtung Hauptwache by Talbot, 1846

Beginnings

Talbot first had the idea for what would become the foundations of modern photography while on holiday at Lake Como, Italy, in 1833. He’d been attempting to draw the scenery, when the idea occurred that it would be much easier if he had some kind of light-sensitive device to do the sketching for him.

Together with his assistant Nicolaas Henneman, Talbot got to work, experimenting with a tiny camera obscura and different coatings for photographic paper – building on the work of experimenters such as Thomas Wedgwood and Nicéphore Niépce, who had captured images on paper with silver salts some years before.

By 1835, he had something: a combination of silver nitrate and common table salt, which he was able to use to create images of beautiful Lacock Abbey and its surrounding gardens, where the Fox Talbot Museum is located today. Talbot and Henneman spent a further four years experimenting and refining their process, and in early 1839, Talbot prepared to give his creation its first showing to the Royal Society. However, it transpired that someone else in another place was about to do the same thing.

Daguerre and Calotypes

Simultaneous inventions are more common than you might expect. For example, Isaac Newton and a German mathematician, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, independently invented calculus in the 17th century, and though history remembers Alexander Graham Bell as the inventor of the telephone, Elisha Gray filed a patent for a similar device.

When Talbot unveiled his first images to the Royal Society in 1839, it was just three weeks after Frenchman Louis Daguerre had displayed his “Daguerreotypes” (pictures made on silver plates) to the French Academy of Sciences.

Though it was simply coincidence, Talbot was understandably annoyed. “I cannot help thinking that a very singular chance (or mischance) has happened to myself, viz. that after having devoted much labour and attention to the perfecting of this invention… the same invention should be announced in France,” he complained in a letter.

SEE ALSO: How to take the ultimate Instagram snap from the edge of space

England monastery in Lacock Abbey by Talbot, 1844

It was Talbot’s inventions that would ultimately be more successful, however. “The daguerreotype… although more popular commercially, was a technological dead end,” Pritchard explains. Talbot’s methods paved the way for what would be an even more significant discovery. He had been making prints with paper sensitised with silver chloride, and though this worked, it required a very long exposure time of at least an hour for a recognisable image to be made. In 1840, however, Talbot discovered that using Gallic acid would allow him to very quickly form a near-invisible image onto paper.

From this, he realised, he’d be able to chemically develop a “positive” print from this latent image onto a separate paper as many times as he needed to. Talbot had developed the first photographic negative, an invention that he called a calotype.

“The discovery of the latent image and development, and the concept of the negative from which any number of positives could be made are perhaps the two most important discoveries [Talbot] made,” Pritchard says.

Talbot’s digital legacy

You could be forgiven for questioning whether Talbot remains relevant today. Though more people are taking photographs than ever before, digital dominates, with analogue imaging now the preserve of enthusiasts. Does anything of Talbot’s legacy remain? We put the question to the experts.

“Talbot’s work is with us in the digital era,” says Pritchard. “We are in a period of transition with many photographers making digital negatives to print digitally, or printing digitally from traditional negatives, which is one reason Photoshop has the option to invert from negative to positive in its menus.”

Kemp agrees: “Every modern image, however generated, that claims to present the visual truth of what can be seen stands in [Talbot and Daguerre’s] legacy,” he says. “As the inventor of the negative process, which allowed the printing of many replicas, Talbot

also stands as the ancestor of technological reproducibility in

photography.”

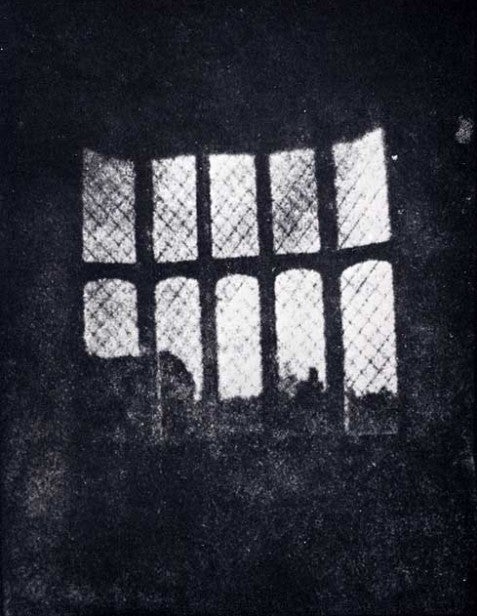

The image above is a positive print from what may be the oldest photographic negative made in a camera, taken by Talbot. He

chose this scene because of the significant contrast of light and dark.

However far the world has moved on, it’s clear that people still care about Talbot and what his discoveries mean. Just last year, both Kemp and Pritchard were involved in a campaign for Oxford University’s Bodleian Libraries to acquire the Fox Talbot archives for £2.25 million. With support from such luminaries as photographer Martin Parr and artist David Hockney, the campaign succeeded.

“There is still much work to be done on Talbot as a pioneer of photography and his other scientific interest,” Pritchard explains. “He is one of the great British polymaths, making the retention of the archive in this country essential.

“The Bodleian Libraries has the expertise and enthusiasm to ensure that the archive is looked after, researched, and importantly, made available to everyone digitally, ” continues Pritchard. “I think we’ll see some exciting discoveries made about Talbot over the next few years.”

Indeed, it does seem right that the work of a British pioneer remains under British care.