Thom Yorke vs Spotify: If you love music, should you use Spotify?

Thom Yorke vs Spotify – who is right?

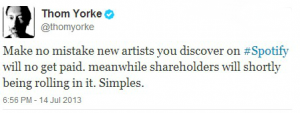

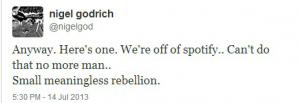

Last week, Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke (then wearing his Atoms For Peace side-project hat) and his producer Nigel Godrich came out against music streaming services, singling out Spotify in particular:

Godrich went on to announce, “Someone gotta say something. It’s bad for new music..

Yorke and Godrich are not the first artists to object to the economics of music streaming, but are they right? Is Spotify really a blight on musician’s careers or are things more complicated?

Put simply: if you love music, should you use Spotify?

The more things change, the more they stay the same?

There is no denying that streaming is a major shift in the way we consume music, but it is not the first. The music industry has been through many such upheavals. As digital rights campaigners are fond of pointing out, the early days of recorded music were rife with protests from live musicians who believed that their livelihoods were threatened by technology that meant anyone could pay once for a performance and then play it was many times as they wished.

Back in the 1800s, music publishers fought pitched battles against sheet music piracy and the shift to digital downloads via services like iTunes was also resisted by many.

Some artists and publishers still argue that digital downloads offer lower royalty payments than they would like but iTunes and its competitors are now firmly entrenched and have proven to be a reliable form of income for many musicians.

Now, it is the turn of streaming services to be singled out as the enemy of the creative arts. Streaming music doesn’t pay, say many musicians and companies like Spotify are making money while the artists suffer.

How does Spotify pay artists?

So, how do artists actually get paid? Spotify would not reveal exact figures but rather pointed me to this article in which their ‘artist in residence’, DA Wallach, runs through the basics.

Payments are based on two different types of rights: mechanical and performance. Performance rights are paid for each ‘performance’ of a track when it is streamed and usually go to artists or to labels, which distribute a percentage to their artists.

Mechanical rights are paid for the right to reproduce a track either physically (on CD for example) or digitally – i.e. to stream it. These are usually paid to music publishers, which will have an agreement to pay a percentage to artists or labels.

Payments are made to rights holders based on a percentage of Spotify’s income. Spotify’s subscription services charge two tiers of fees for differing levels of access and the ability to cache music on mobile devices. There is also a free service which is supported by non-skippable ads inserted between tracks. As well as being an irritant designed to encourage payment, Spotify makes money from advertisers.

These two revenue streams are combined and Spotify pays a percentage (70% at the time that article was written, 2012) in performance rights plus a capped percentage in mechanical rights. From an artist’s point of view, the process is further obscured by the fact that the money tends to go to their label, which will then give them a smaller percentage based on whatever contract is in place.

“At the end of the day,” says Wallach, “the indie artist is not at a disadvantage compared to a major label artist, and we feel that all artists are being compensated fairly.”

What do musicians say?

I spoke to two musicians who have their work on Spotify: Mary Epworth, a singer-songwriter whose debut album Dream Life was released in 2012 to critical acclaim; and Pete Gofton, who has music on Spotify from his former band Kenickie (alongside his sister, Lauren Laverne) as well as his two solo projects, J Xaverre and George Washington Brown.

I spoke to two musicians who have their work on Spotify: Mary Epworth, a singer-songwriter whose debut album Dream Life was released in 2012 to critical acclaim; and Pete Gofton, who has music on Spotify from his former band Kenickie (alongside his sister, Lauren Laverne) as well as his two solo projects, J Xaverre and George Washington Brown.

Pete has been creating music for over two decades and now works in further education as a music technology teacher, while still performing and recording. Neither sees Spotify as being a significant source of income at the moment.

“It’s not significant, or worth getting excited about in my case,” says Epworth, “but it’s not the 0.001p I was expecting given some of the horror stories out there.”

“Compared to national radio or TV play, the amount you get per play is tiny.” says Pete. “But in all probability the amount of plays on Spotify and YouTube etc are many more than you’re likely to get on daytime (or even night-time) Radio 1, so it’s a trade-off. In my case, it’s really a meaningless amount of money. I’m not losing sleep over it.”

That comparison with radio is often brought up by Spotify’s critics but, as Gofton points out, it’s not really a like-for-like comparison. Spotify pays a very small amount per play – often a fraction of a penny – and in comparison to the rates paid for a play on national radio it seems almost comically low. Look a little closer, however, and it may not be so bad.

UK radio pays comparatively well compared to stations in the US. For a typical three and a half-minute track on Radio 2 (the biggest UK station in terms of listener figures) you could expect to receive roughly £60, but that ‘play’ is actually heard by as many as nine million listeners. A single Spotify play comes out of the headphones or laptop speakers of just one listener. When seen in those terms, £60 for nine million listens is a tiny amount and that micropayment from Spotify actually comes out rather better.

The Real Problem…

T he real problem facing musicians is not simply that Spotify or the many other competing services don’t pay well but rather that, across the board, it is extremely hard to make a living by playing music.

he real problem facing musicians is not simply that Spotify or the many other competing services don’t pay well but rather that, across the board, it is extremely hard to make a living by playing music.

“The music you make is just one small aspect of the ‘brand’ that you’re selling – yourself,” claims Gofton. “

“You use free music as a way to draw fans to your gigs, buy merchandise, visit your YouTube or Facebook page (where you’ve entered into a partnership agreement with sponsors so you get a percentage of the ad revenue) and hopefully getting your song on an ad.”

Mary Epworth says she can see the value of Spotify as a promotional tool, too.

“These services, and YouTube as well certainly do make your music available to more people, along with playing gigs, being on the radio etc. That’s not to say that it’s always worth getting stuff out there for free, you have to weigh up the pros and cons.

“I don’t really see Spotify as a problem, more just part of the landscape of the music industry in 2013. I’m not sure we’ve yet worked out what music is worth to a consumer now, and how we expect them to pay. I’m curious to see how things end up.”

The non-profit group Future Of Music Coalition created a list of 42 Ways to Make Money As An Independent Musician, which attempts to show how it is still possible to earn money from music. It looks like solid advice to this non-musician, but it doesn’t have much in common with the fantasy of being a rock or pop star.

“Tying together all these different revenue streams is the only way you can hope to make money like the good old days,” says Gofton. “It’s incredibly unsexy, but that’s where being a professional musician is right now. The days of someone writing ten songs and expecting to make their living through advances. tour and sales is gone.”

Spotify vs Piracy

Another important thing to consider is the impact the services like Spotify have had on music piracy. In Norway, where Spotify is enormously popular, streaming now accounts for 66% of all music sales and overall sales were up 17% in the first quarter of this year.

A recent survey estimated that music piracy in Norway has fallen by nearly 82% in the last five years. It could be argued that even if the revenues from streaming are small, compared to the revenue from pirated music – i.e. nothing – they are a welcome bonus.

Spotify may not be capable of funding everyone’s private jet and pool party excesses at the moment, but given the way it distributes money as a percentage of its income there could be brighter news around the corner.

Ironically, it will require more musicians and labels to accept it as a valid market for their music and keep their music available. But if Spotify continues to grow at current rates then the number of paying customers, increased ad sales and – crucially – the number of people wanting to listen to their music could reach a point where bands don’t feel quite so short-changed.